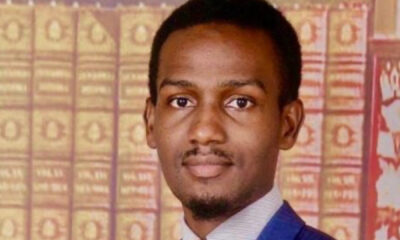

The Department of State Services has reopened investigations into the 2019 disappearance of Abubakar Idris, popularly known as Dadiyata, and is set to invite suspects in connection with the case.

Dadiyata, a lecturer at the Federal University Dutsinma, Katsina State, was declared missing on August 1, 2019, after gunmen reportedly took him from his residence in Kaduna.

His whereabouts remain unknown nearly seven years later.

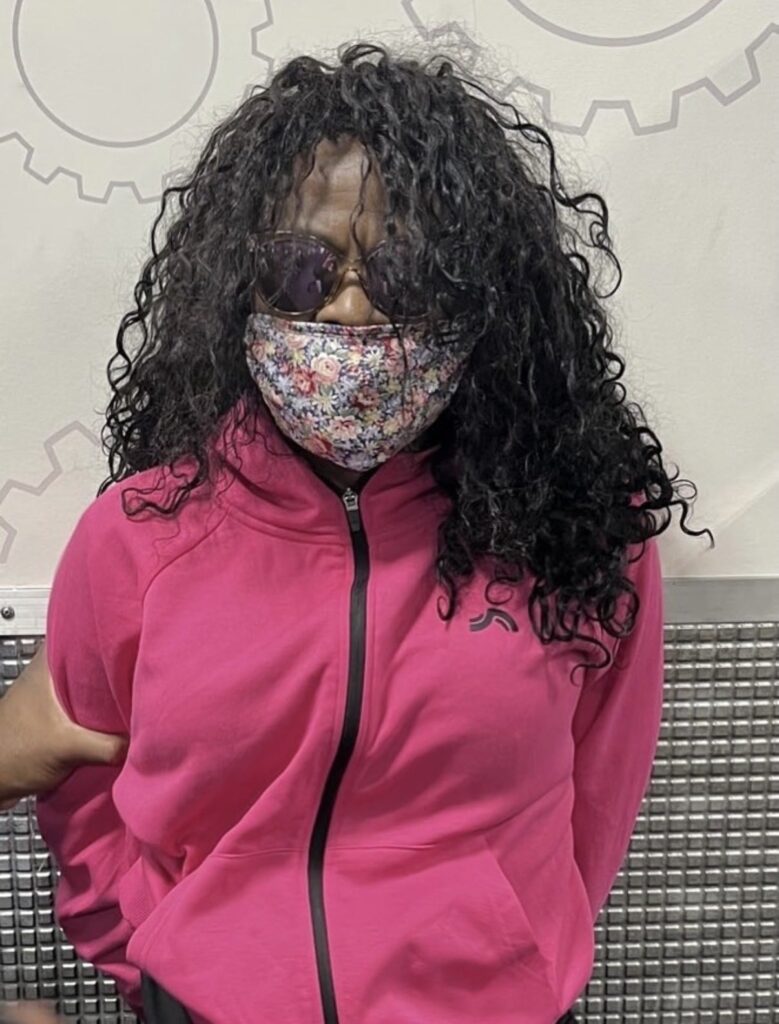

The development comes as Kadijah, the wife of social media commentator and critic, expressed fresh worries over her husband’s disappearance.

She spoke in a video interview with Ambassador-designate Reno Omokri, which was released on his X handle on Thursday.

Omokri, who visited the mother of two at her residence, sought support for Kadijah and her children, pledging to get justice for her.

“We pray that one day, he will come back,” Kadijah said when asked what she had to say about her husband’s disappearance over the years, especially given recent comments made by former Kaduna State Governor, Nasir El-Rufai.

Appealing to Nigerians, she said, “They should please do whatever they can to help us know his whereabouts, if he’s alive or not.”

Omokri further asked Kadijah what she had to say about an old comment made about her husband that suggested “mockery.”

“It was somebody who showed me (the post) because I didn’t have a phone at that time,” she said of the 2019 comment reportedly made by the son of a former Kaduna State Governor.

The post had read, “Those same clowns who encouraged him when he was creating false stories and capitalising on lies that could endanger lives solely for political ends are the same individuals trending hashtags asking, ‘#WhereisDadiyata.’

“Dangerous lies in the public space have consequences. I felt bad about it (the comment). I can’t even explain,” Kadijah stated in the video.

She further narrated how her husband was abducted as he alighted from his car in their compound on August 2, 2019, saying she watched from the window as it happened.

Assuring Kadijah of Dadiyata’s safe return if he is alive, and justice in the unlikely event of his death, Omokri empathised with the woman and sought assistance for the family.

He appealed to the Governor of Kaduna State, Uba Sani, for “whatever he can do for them… to help their living conditions, probably relocate them, help their education, or help the mother with a job. Nigeria owes a duty of care to this family for what has happened to them.”

Dadiyata, a lecturer and online commentator, was abducted on August 2, 2019, by unidentified gunmen as he drove into his home in Barnawa, Kaduna.

The incident has continued to attract public attention and demands for accountability.

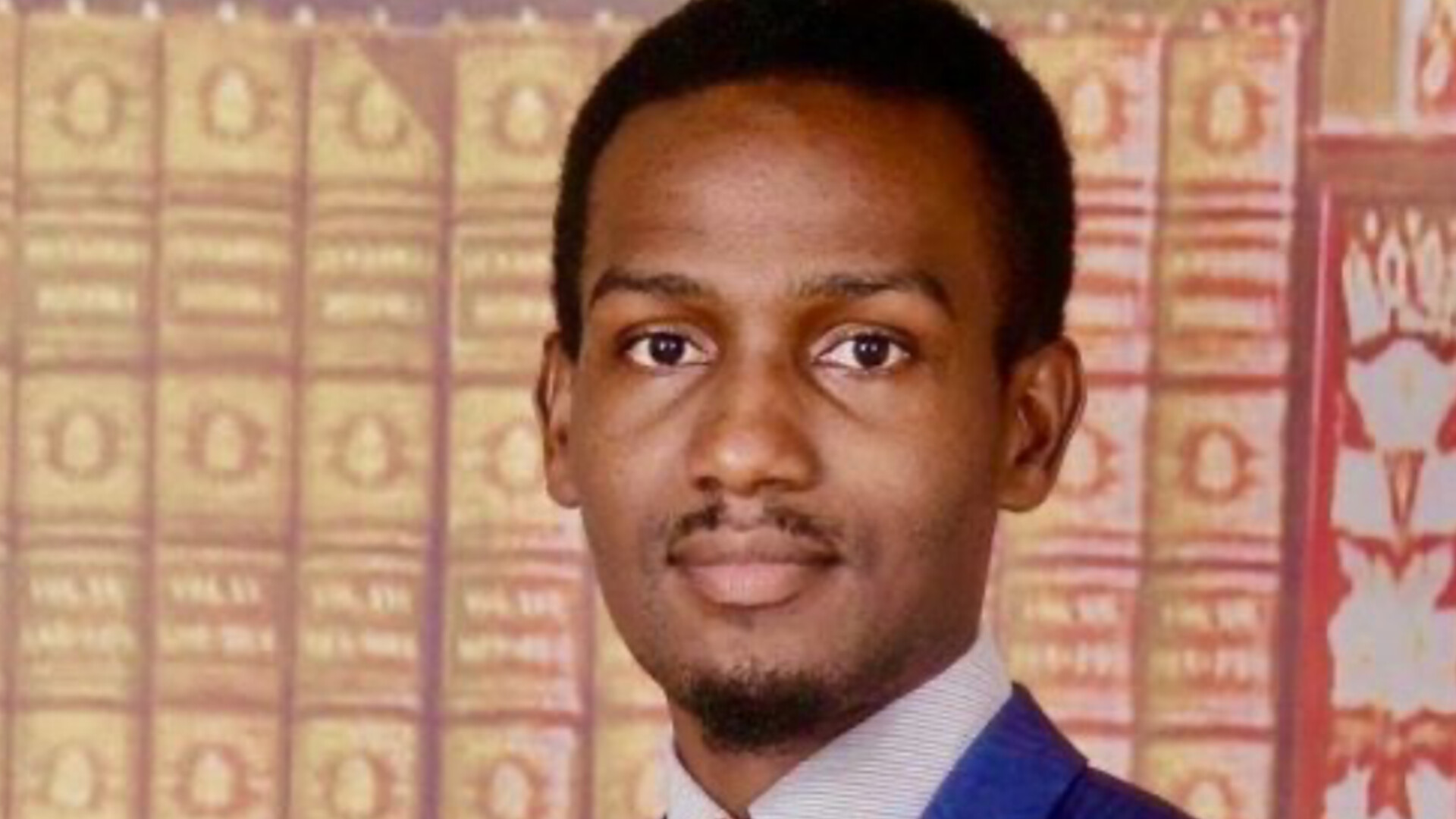

Dadiyata’s matter resurfaced on February 14, 2026, when El-Rufai denied any involvement in the case and argued that the missing commentator was primarily critical of the Kano administration rather than the Kaduna State government.

“Dadiyata was not a fierce critic of the Kaduna State government. He was a fierce critic of the Kano State government.

“He is a Kwankwasiya guy; he lives in Kaduna and lectures at a university in Katsina State, but is a fierce critic not of Kaduna State. Go and review his timeline,” he said.

El-Rufai further stated that he was unaware of Dadiyata before the abduction was reported to the police.

“It was Ganduje that was his problem. I didn’t even know him. We only got the report of Dadiyata’s existence and the fact that he lives in Kaduna State after the family reported to the police that he was abducted as he was returning home in the evening.

“If anybody is to be asked about the disappearance of Dadiyata, it is the Kano State Government; it has nothing to do with the Kaduna State Government. We didn’t even know he existed,” he said.

Reacting, former Kano State governor, Abdullahi Ganduje, dismissed being linked to the case in a statement issued by his former Commissioner for Information and Internal Affairs, Muhammad Garba.

He described the claims as “reckless, unfounded, and a clear attempt to shift responsibility for an incident that occurred entirely within Kaduna State.”

According to Ganduje, Dadiyata was widely known in Kaduna for his criticism of the state government.

“Everyone in Kaduna knew the nature of the criticism he made and who it was directed at,” he said.

A security source told The PUNCH that the DSS recently seized El-Rufai’s passport at the Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport, Abuja, to prevent him from travelling abroad while investigations are ongoing.

“The DSS has reopened the case of the 2019 disappearance in Kaduna of a renowned government critic, Abubakar Idris, better known as Dadiyata, and several other cases of missing persons.

“El’Rufai is fully aware that the DSS is investigating him and his two sons for Dadiyata’s kidnapping.

The Service was reported to have reopened the case and was set to invite El-Rufai’s sons for questioning over the matter.

punch.ng

FOLLOW US ON:

FACEBOOK

TWITTER

PINTEREST

TIKTOK

YOUTUBE

LINKEDIN

TUMBLR

INSTAGRAM