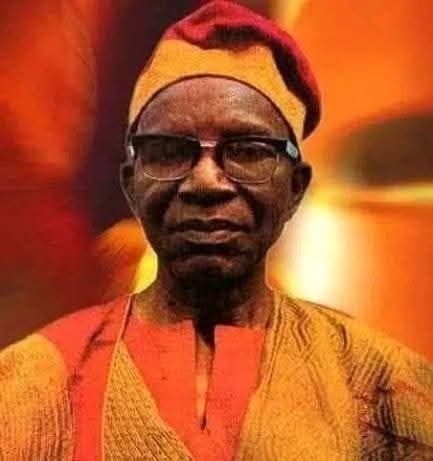

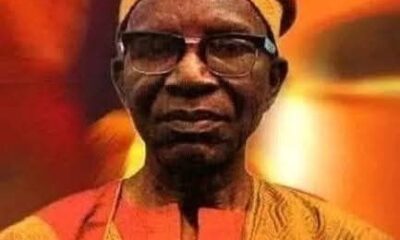

Michael Adekunle Ajasin remains one of the most respected figures in Nigeria’s political and educational history, remembered for his intellectual depth, personal integrity, and unwavering commitment to democratic ideals and public education.

Born on 28 November 1908 in Owo, present-day Ondo State, Ajasin’s early life was shaped by discipline, learning, and service. He attended St. Andrew’s College, Oyo between 1924 and 1927, one of the foremost teacher-training institutions in colonial Nigeria. After qualifying as a teacher, he worked in the profession for several years, laying the foundation for what would become a lifelong dedication to education.

In 1943, Ajasin gained admission to Fourah Bay College, Sierra Leone, then one of the most prestigious higher institutions for Africans in British West Africa. He graduated in June 1946 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English, Modern History, and Economics. Determined to deepen his professional competence, he proceeded to the Institute of Education, University of London, where he obtained a Postgraduate Diploma in Education in June 1947.

Family Life

Ajasin married Babafunke Tenabe, also a teacher, on 12 January 1939. Their marriage produced four children—two sons and two daughters. One of his daughters, Mrs Olajumoke Anifowoshe, distinguished herself in public service, becoming Attorney-General and Commissioner for Justice in Ondo State, further reflecting the family’s strong tradition of civic engagement.

Educational Leadership

On 12 September 1947, Michael Adekunle Ajasin was appointed Principal of Imade College, Owo. His tenure was marked by visionary leadership and an aggressive staff development programme. Notably, he facilitated opportunities for teachers to pursue further training at University College, Ibadan, at a time when such advancement was rare.

In December 1962, Ajasin left Imade College to establish Owo High School, where he served as founder, proprietor, and first principal from January 1963 to August 1975. Under his leadership, the school earned a reputation for academic excellence and discipline, reinforcing his belief that education was the most effective instrument for social transformation.

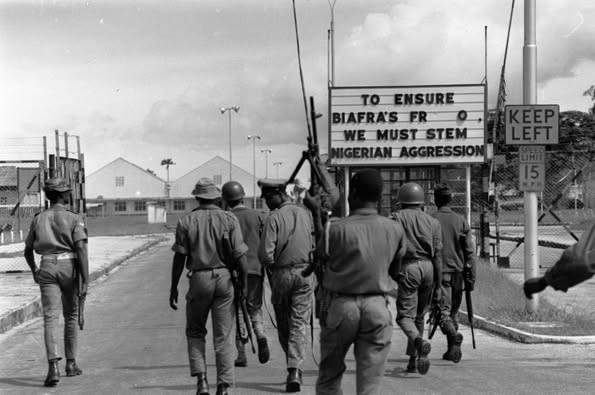

Political Thought and Early Activism

Ajasin was deeply involved in Nigeria’s nationalist and pre-independence politics. In 1951, he authored a policy paper that later became the education blueprint of the Action Group (AG), boldly advocating free education at all levels. This proposal would later be implemented in Western Nigeria under Chief Obafemi Awolowo and remains one of the most impactful social policies in Nigerian history.

He was among the founders of the Action Group, a party whose ideology centred on immediate independence from Britain, universal healthcare, and the eradication of poverty through sound economic planning. During the 1950s, Ajasin served as National Vice President of the Action Group.

Legislative and Local Government Service

Ajasin’s political career expanded steadily. He became an elected ward councillor, then Chairman of Owo District Council, which covered Owo and surrounding communities such as Idashen, Emure-Ile, Ipele, Arimogija, Ute, Elerenla, and Okeluse.

In 1954, he was elected to the Federal House of Representatives in Lagos, serving as a federal legislator until 1966, when military rule interrupted Nigeria’s First Republic. His years in parliament were characterised by advocacy for education, regional development, and constitutional governance.

Return to Politics and Governorship

In 1976, Ajasin became Chairman of Owo Local Government. With the return to civilian rule, he joined the Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN), the ideological successor to the Action Group.

In 1979, he was elected Governor of Ondo State, with Akin Omoboriowo as his deputy. His administration prioritised education, rural development, and fiscal discipline. However, political tensions emerged when Omoboriowo defected to the National Party of Nigeria (NPN) and contested the 1983 gubernatorial election against him. Although Omoboriowo was initially declared winner, the results were later annulled, and Ajasin was sworn in for a second term.

His tenure was abruptly terminated by the military coup of 31 December 1983, which brought General Muhammadu Buhari to power.

Integrity and Personal Example

Michael Adekunle Ajasin was widely admired for his personal honesty. Reflecting on his years in office, he famously stated:

“I came into office in October 1979 with a set of my own rich native dresses and left office in December 1983 with the same set of dresses; no addition and no subtraction.”

He further noted that he owned no personal cars upon leaving office, having exhausted the two he had before assuming governorship. This statement has since become a benchmark for ethical leadership in Nigeria.

Pro-Democracy Struggle

In the 1990s, Ajasin emerged as a leading elder statesman within the National Democratic Coalition (NADECO), which opposed military dictatorship and demanded the validation of Chief M.K.O. Abiola’s annulled June 12, 1993 presidential mandate.

In 1995, he was arrested by the Abacha military regime, alongside 39 other activists, for participating in what the government termed an illegal political meeting—an episode that underscored his lifelong commitment to democracy and civil liberties.

Educational Legacy

As governor, Ajasin signed into law the establishment of Ondo State University in 1982, located in Ado-Ekiti (now in Ekiti State). In 2000, during the administration of Chief Adebayo Adefarati, a new university in Akungba-Akoko was named Adekunle Ajasin University in his honour. He also played a key role in the establishment of The Polytechnic, Owo.

Michael Adekunle Ajasin stands as a rare example of a Nigerian leader whose intellectual rigour, moral discipline, and public service aligned seamlessly. His legacy lives on through the institutions he built, the policies he shaped, and the enduring example of integrity he set in public life.

Source:

Ondo State Government Historical Records; Nigerian Political Biographies; Action Group Party Archives; Adekunle Ajasin University Documentation

FOLLOW US ON:

FACEBOOK

TWITTER

PINTEREST

TIKTOK

YOUTUBE

LINKEDIN

TUMBLR

INSTAGRAM

Politics23 hours ago

Politics23 hours ago

Lifestyle23 hours ago

Lifestyle23 hours ago

Business23 hours ago

Business23 hours ago

Lifestyle24 hours ago

Lifestyle24 hours ago

Sports23 hours ago

Sports23 hours ago

News22 hours ago

News22 hours ago

Lifestyle13 hours ago

Lifestyle13 hours ago

News23 hours ago

News23 hours ago