Lifestyle

PHOTOS: 7 Beautiful Traditional Yoruba Hairstyles – Irun Dídì Ni Ayé Àtijọ́

Published

4 months agoon

In Yoruba culture, hair is more than just a part of the body; it is a crown, a symbol of identity, and an expression of creativity. Among the Yoruba people, hairstyles in the olden days were of high cultural relevance, a source of storytelling, an index of social status, and a mirror to personal and collective identity. Whether braided, threaded, or even decorated with elaborate adornments, each hairstyle told something different about the age, marital status, spiritual condition, or even mood of the wearer.

Traditional Yoruba hairstyles were not only a testament to the artistic brilliance of the Yoruba people but also a cherished aspect of our heritage. Created with care, using natural oils, combs, threads, and sometimes beads or cowries, these hairstyles required skill, patience, and a deep understanding of the craft. More than just a fashion statement, they were a celebration of Yoruba values, connecting us to our ancestors and community.

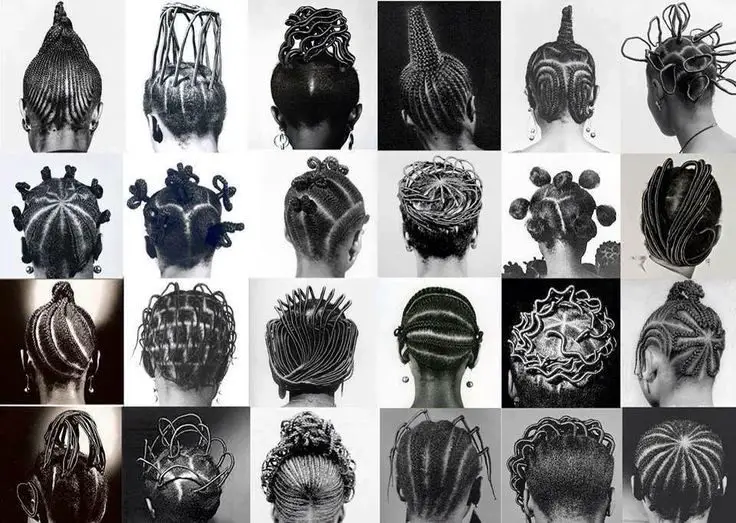

This article explores seven iconic hairstyles from olden-day Yoruba communities. Basically, there are two main ways Yoruba women traditionally styled their hair back in the day: Ìrun Dídì (cornrows) and Ìrun Kíkó (threaded hairstyles). We will take a look at the threaded styles and different cornrow styles (as it had many varieties). Each of these natural hairstyles represents the rich tapestry of culture of Yoruba people and takes you back in time when each braid and bead was an indication of something, and everything had a reason behind it.

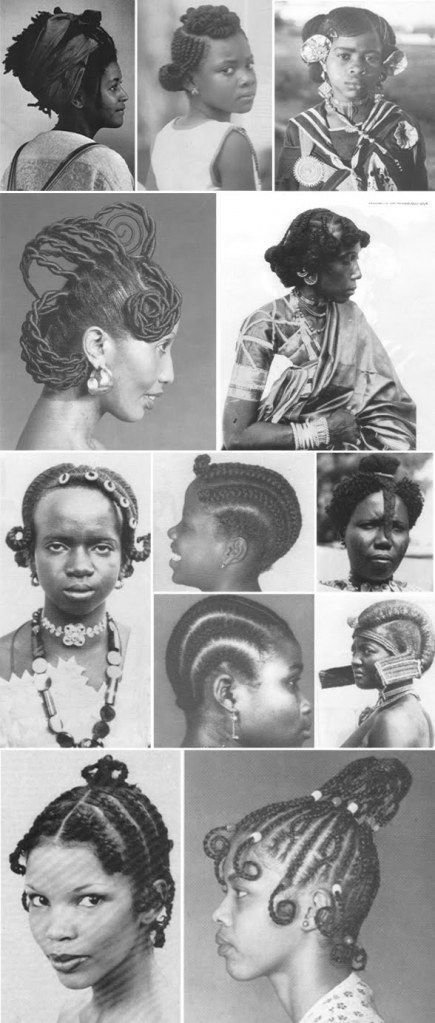

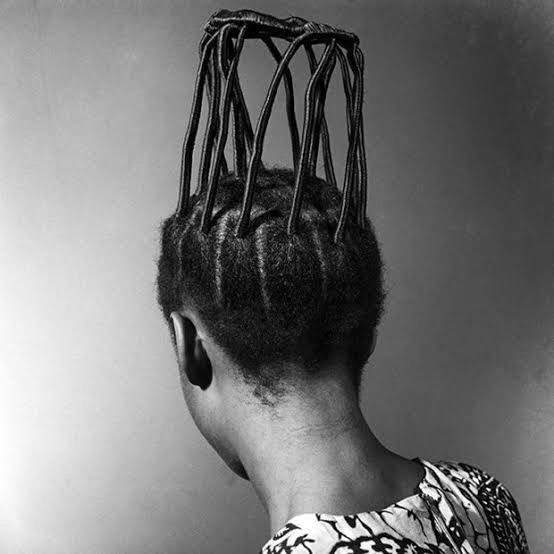

1. Ìrun Kíkó: The Art of Threading Hair

Ìrun Kíkó, also known as hair threading, is a traditional Yoruba hairstyle involving wrapping sections of hair with black thread to achieve a unique and eye-catching style. This method has been both decorative and protective in nature, hence being one of the cornerstones of Yoruba hair culture through generations.

Cultural Significance

In the Yoruba culture, Ìrun Kíkó was more than a hairdo. The style allowed women to be creative in designing several patterns and shapes with threaded hair. Ìrun Kíkó had practical uses other than aesthetics: it protected hair from damage and breakages while promoting hair length retention.

The threading technique also highlighted the natural beauty and versatility of African hair, symbolizing pride in heritage. Special events, such as weddings and festivals, were times when such a hairstyle was commonplace.

How It Was Done

This hairstyle was made using a special black thread made from plastic or wool. A section of hair is made and then each is wrapped with the thread tightly from its roots to the ends. Depending on the desired outcome, it may be manipulated into several forms such as straight, spiral, or curved shapes.

Ìrun Kíkó can be worn in styles ranging from very simple, practical wear to intricate statement wear. Like cornrows, it also can be made into several variations from looping and crowns to different geometric shapes.

One of these variations include the Police Cap hairstyle women wore during the colonial and post-colonial era. In this style, the threaded sections of the hair are stylishly brought to one side of the front of the face and held down, looking like a police cap (beret).

Present-Day Influence

While in the old days, Ìrun Kíkó was very popular; of late, people have gone back to appreciating this hairstyle for its protective nature and its ability to effectively stretch natural hair.

2. Ṣùkú

One of the most iconic and enduring hairstyles from olden-day Yoruba communities is Ṣùkú. This style is produced by weaving the hair up into an upward bun to give it an elegant and regal look. The name Ṣùkú itself, meaning “round” or “circular,” comes from this shape of the hairstyle.

Cultural Significance

Sùkú had great cultural significance, depicting beauty, youth, and energy. It was normally worn by young women, especially brides-to-be, as part of their wedding preparations or during festive events. This hair was also considered indicative of femininity and preparedness for new responsibilities.

The style was also commonly used by women in communal settings and signified shared values as well as the unity of the Yoruba tradition. It was a versatile hairstyle for both celebrations and everyday life.

How It Was Done:

The making of Sùkú is a process involving skill and precision: to begin, a stylist would section the hair into parts, weaving each braid upward toward the center of the head. Sometimes the hair was divided into symmetrical patterns or artistic shapes and then gathered into a bun. The use of natural oils, such as coconut oil or shea butter, ensured the hair was soft, shiny, and easy to braid.

In some instances, Sùkú was ornamented with decorations such as beads or cowries for beautification. These accessories often had their own meanings, symbolizing wealth, fertility, or spiritual protection.

Present-Day Influence

Although Sùkú originated in olden days, its influence can still be felt within the modern Yoruba communities.

Today, Sùkú hairstyles are worn during cultural festivals, weddings, and even as everyday hairstyles.

The modern stylists have reimagined Sùkú, combining traditional techniques with modern aesthetics to keep this timeless hairstyle alive.

Sùkú remains a testament to the ingenuity and artistry of the Yoruba people, reminding us of the beauty and significance of our cultural heritage.

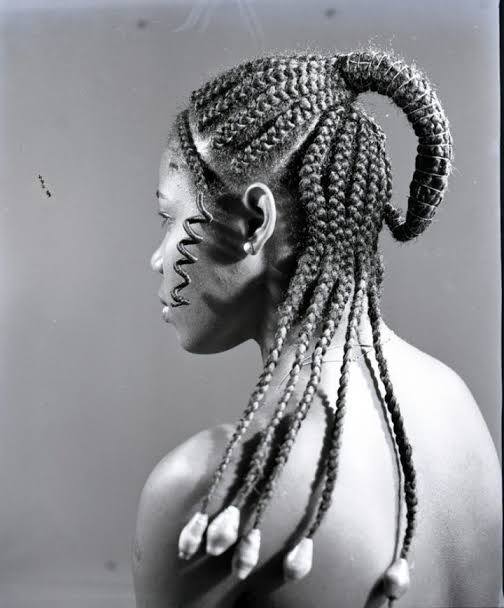

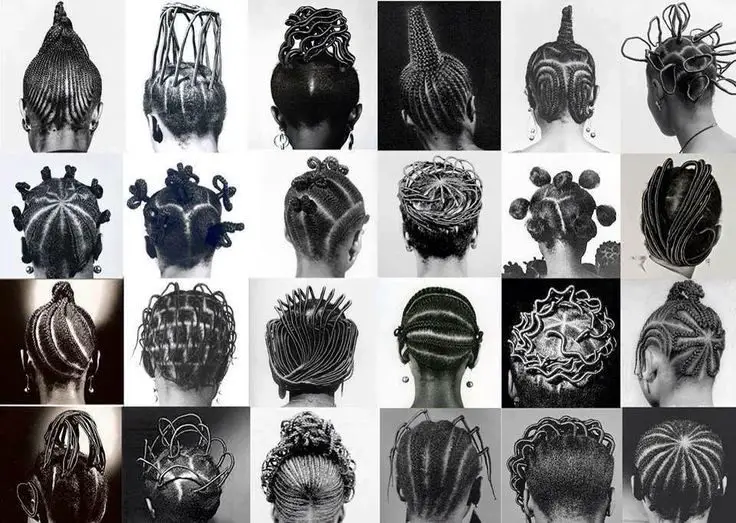

3. Kolésè:

The Beauty of Natural Coils

The Kolésè is a traditional Yoruba style in which cornrows run from the front or top of the head to the back, close to the neck. This peculiar style is distinguished by the absence of “leg” braids -meaning the braids do not go down the neck but end near the back of the head. The clean, structured cornrows are a representation of natural elegance, making Kolésè a timeless and distinctive look.

Cultural Significance

The name Kolésè is derived from the texture of the hair that was common among Yoruba women in precolonial times. The women often had curly or coily hair, and the hair ends would not lie flat; they would spring up naturally. This no doubt inspired the naming as “Kolésè,” a name closely mirroring the curling motion of the hair’s natural ends.

The Kolésè hairstyle in Yoruba culture is a proud symbol of one’s natural beauty and heritage. More than anything, it was not a fashion statement but reflected an identity and attachment to the wearer’s roots. The style accentuated the hair in its natural texture and hence spoke volumes of the strength and beauty of coiled hair.

How It Was Done:

Kolésè was made by equally parting the hair, then plaiting them into neat cornrows. These cornrows would begin from the front or top of the head, working their way to the back of the head near the neck, but won’t continue down the neck because of the natural hair texture (or by manually coiling the braid end). The cornrows were meant to be tightly and neatly drawn to show off clean lines and curl of the natural hair at the end.

For ceremonial occasions, Kolésè could be further adorned with accessories like beads or cowrie shells to enhance the style.

Present-Day Influence

The Kolésè hairstyle remains influential even in today’s natural hairstyling trends. It has been in the spotlight on social media recently because of its close similarity to the signature look of the world-famous and incredible singer-songwriter, Alicia Keys.

Many people with curly or coily hair wear hairstyles that reflect Kolésè as a way of paying homage to their cultural heritage by embracing their natural beauty. The braiding technique may vary slightly with modern tools, but the essence of Kolésè -celebrating natural, coiled hair- remains an important part of contemporary African hair culture.

4. Korobá:

The Upturned Basket Style

Korobá is one of the most recognizable and enduring hairstyles in Yoruba culture. Its name comes from the striking resemblance it holds with an upturned bucket. This distinctive design features braids that go from the center of the head outward to all sides, creating a basket-like appearance that is both elegant and practical.

Cultural Significance

The Korobá hairstyle has long been one of the symbols of beauty and cultural pride among the women of Yoruba. Its design reflects resourcefulness and creativity, with Nigerian traditions reflecting unity and balance in its neat and symmetrical structure. The style was popular for everyday life as well as festive occasions, making it a versatile choice for both simplicity and sophistication.

How It Was Made:

In creating Korobá, the stylist starts from the top of the head, braiding small, even sections outward in a circle. The outcome is clean and symmetrical cornrows that bring out the wearer’s natural features while exuding cultural elegance.

The style could be made more elaborate with beads, cowries, or colorful threads to give it a festive look and make it fit for weddings, ceremonies, or other special events.

Present-Day Influence

The Korobá hairstyle has remained a favorite among ladies who want to identify with their cultural heritage and still look timeless. The hairstyle has seen some modern variations, like incorporating longer extensions or bold colors. It continues being a go-to style for people wanting a unique and traditional look and has become used for photoshoots for this same reason.

With its rich history and its special aesthetic, Korobá stands as testimony to the artistry and genius of Yoruba hairstyling traditions.

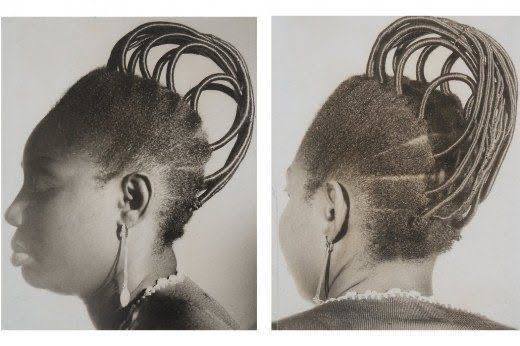

5. Èkó Bridge:

A Bold Symbol of Lagos

The Èkó Bridge hairstyle is an inspired and symbolic Yoruba hairstyle, representing some of the major bridges in Lagos, Nigeria, such as the Eko Bridge itself. This style captures the essence of urban life and connectivity in Lagos, the bustling city often considered the heartbeat of Nigeria.

Cultural Significance

The name of this style is derived from the famous Eko Bridge in Lagos and signifies the city’s importance as a hub of activity and progress. The Èkó Bridge hairstyle was a form of art and a means of celebrating significant landmarks, events, and social concepts. It was mostly worn for special occasions and displayed a mixture of ingenuity and pride in the heritage.

How It Is Made:

In this style, the hair is parted into about 10 sections. Each section is then threaded and put together to form something similar to a bridge over the middle of the head. This is its focal point resembling an actual bridge with its characteristic arch and supporting structure.

To enhance the design, the stylist carefully arranges the braids to create a symmetrical, eye-catching pattern. The result is a hairstyle that not only stands out but also carries deep cultural symbolism.

6. Ìpàkó Àlèdè

Ipakò Alède is a Yoruba traditional hairstyle made with straight cornrows running from the back of the head to the front. The term ipako alède describes how the braids are set in the shape of the “occiput of a pig”. In this hairstyle, cornrows are beautifully woven to a sleek and orderly pattern straight to the face from the nape of the neck forward to the forehead.

It symbolizes neatness and good discipline in nature, often reserved for formal or ceremonial purposes. It is a hairstyle that intends to show the skill it takes to achieve a symmetrical look, with perfect alignments of each cornrow.

In Yoruba culture, the Ìpàkó Àlèdè was typically worn by women to show regard for their appearance and ability to keep a very elaborate hairstyle, which was also supposed to be an indicator of social status and attention to detail.

7. Pàtéwó

Pàtéwó, which literally means “clap your hands” in Yoruba, is a hairstyle symbolic and functional at the same time. It gets this name from how the braids are made to meet in the middle of the head, like two hands meeting either to pray or to clap. It is somewhat similar to the commonly known ṣádé hairstyle.

Cultural Significance:

Pàtéwó was generally a natural hairstyle for kids and women during big cultural events or just as a casual wear because it looks neat and elegant.

How It Was Made:

The hair is partitioned into two portions in making Pàtéwó. Each portion is cornrowed toward the center of the head, where the two sides meet to provide a symmetrical and clean finish. The braids are usually fine and quite close together so that the style will look neat and tidy. The middle meeting point can either be done with beads and cowries or remain empty, depending on the choice of the person wearing it……!

FOLLOW US ON:

You may like

Lifestyle

PHOTOS: Meet Prince Abimbola Onabanjo Of Ijebu Land(the New Awujale Of Ijebu Land Elect)

Published

2 days agoon

January 9, 2026

I have heard that one of the strong ọmọ ọba who may likely clinch the highly exalted stool of the next Awujale of Ijebu Land, according to some reports, is Prince Abimbola Onabanjo.

Prince Abimbola Onabanjo hails from the royal family of Fusengbuwa in Ijebu-Ode. He is a 2007 graduate of Banking and Finance from Lagos State University (LASU) and has undergone several Graduate Business Executive trainings at prestigious institutions, including Harvard Business School, Columbia Business School, and The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Popularly known as Prince Abimbola among friends in Ijebu and Lagos, he is a young businessman with close to 20 years of experience. He is the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Kleensteps Holdings, Extol Securities, and KMF Oils and Gas Limited.

Beyond his business accomplishments, he is also a philanthropist who has contributed immensely to several charitable projects across Ijebu Land in recent years. Few years ago, he reportedly committed 25m naira to 25 schools across Ijebu Ode as part of his vision for long term development of the land.

The young Prince had also in the past support the rehabilitation of road projects in Ijebu including the Balogun Court, Ojusgagbola Avenue, Abusalawu Street, and sections of Osipitan road. And there are many community projects like this, done from time to time.

Well, as the selection and ascension process is currently ongoing, I pray that the family heads, in choosing among the eligible princes, will do the needful.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about another prince, Dr. Adekunle Hassan, a 75-year-old ophthalmologist.

Many reactions suggested that people would prefer the next Awujale to be young rather than elderly. Whatever the reasons may be, I hope this charming Prince Abimbola satisfies that wish 😊.

My foremost concern is fairness in the process and that only the legitimate and rightful ruling house as recognised in the Gazette should be allowed to produce the next king, and not ganusi from any corner. This is how we properly protect our heritage for posterity.

As a people, we must learn to wait for our turn.

I also hope that whoever emerges as the next Awujale will be blessed with wisdom, knowledge, and deep understanding of the sacred role of a traditional ruler in Yorubaland, as one who will be seen as a father to all, without prejudice to social class, religion, or age.

And one who will rule with wisdom and peace, and bring meaningful development to the land through the support of sons and daughters of Ijebu, as well as through strong networks in society.

May the best prince emerge.

FOLLOW US ON:

Lifestyle

PHOTOS: Nollywood Actress Allwell Ademola was finally la!d to rest in Lagos

Published

2 days agoon

January 9, 2026

Nollywood actress and film producer Allwell Ademola was laid to rest on Friday at Atan Cemetery, Yaba, Lagos State.

It was reported that the actress died on December 27, 2025, at the age of 49.

Colleagues from the film industry, including Afeez Abiodun, Rotimi Salami, Kunle Afod, and Abiola Adebayo, among others, attended the burial to pay their last respects to the actress, who was widely known for her role as “Mama Kate” in the 2018 film “Ile Wa.”

In viral videos seen by this newspaper, the actors who attended the final rites were visibly emotional, breaking down in tears as they poured sand on Ms Ademola’s coffin, which had already been lowered into the grave.

During a brief sermon at the cemetery, the pastor who officiated the burial urged attendees to reflect on their lives while they still had the opportunity.

Reminder

He said the burial served as a reminder that everyone would one day face the same end.

He added that the moment should prompt deep reflection on how one’s life journey would conclude, particularly for those harbouring malice or engaging in wrongdoing.

The pastor said, “Then you will discover that nobody has time. The will of God is that this should help us mend our ways before our Maker. He said the righteous will always consider this in their hearts. What are we going to do with this? She has lived her life. She has run the race and has gone to meet her maker, but what we are doing here is for you and me. As for her, she is rejoicing in the bosom of Abraham.

“How will you end your journey? That malice, wickedness, “I will not agree” — who knows what is next? That is the million-dollar question before us today. Because in the next few days, nature has a way of putting forgetfulness in things. But will you remember that one day it will be my turn, just as it is her turn today? What God expects of us when we see things like this is to look up to God and say, ‘Father, help me to make the best of the time that is left.’”

Candlelight procession and service of songs

At the candlelight procession and service of songs, actors gathered to offer special prayers in memory of their late colleague.

The event, which took place on Thursday, was attended by prominent figures in the industry, including Odunlade Adekola, Saheed Balogun, Bolaji Amusan, Iyabo Ojo, Fausat Balogun, Eniola Ajao and Fathia Balogun. Many attendees wore customised white T-shirts bearing Ademola’s portrait as a mark of tribute.

In an emotional moment captured on video, Salami, widely regarded as one of Ms Ademola’s closest friends in the industry, delivered a heartfelt tribute.

Fighting back tears, he asked for forgiveness on behalf of the late actress.

“If there’s anyone Allwell has offended, directly or indirectly, please, forgive her and keep praying for her. I think the only thing we can actually do is find a way, in unity, to keep her legacy. Even if she’s gone, let all that she has done stay with us and be with us.”

Salami also announced that he would offer one day of free work to anyone who approached him for a film project.

Apology from Allwell’s brother

Meanwhile, one of the late actress’s brothers issued an apology to actress Ojo over remarks he had made following his sister’s death.

He offered the apology during the service of songs held in her honour. Previously, a video that went viral showed him criticising some of her colleagues for their public tributes at the time of her passing.

In the video, he said, “All the ‘Rest in Peace’ messages and public displays of love are fake and hypocritical. Where was this love when she was alive? When she produced Eniobanke, none of you promoted it. You all claimed to be friends, yet you never supported her work or career, even though she supported many of you. During the Jagun Jagun production, no one called her or offered her a role.”

“Some of you, the likes of Lateef Adedimeji, Owonikoko, Iyabo Ojo and others, came to our house to shoot movies, yet you never found it worthy to stand by her. If you couldn’t support her while she was alive, don’t perform loyalty now that she is gone.”

However, Ojo, a mother of two, responded publicly to the claims, affirming that she had supported the late actress during her lifetime.

She wrote, “I oversupported your sister when she was alive, when she was building her career as a Producer and director, I featured in her movies countless times for free, and I also supported her financially and emotionally. May her beautiful soul continue to rest in perfect peace,” she said.

While apologising, he said, “Please ma, don’t be offended. I did not mean to abuse you; I was not referring to you at all.”

FOLLOW US ON:

One major issue that caught the attention of Nigerian writers, historians, journalists and linguists amongst others in January 2020, was the adoption of 29 Nigerian coinages and words from, especially Yoruba and Hausa languages, into the Oxford English Dictionary. Words and colloquial, such as danfo, okada, buka, k-leg, to eat money, next tomorrow, chop-chop, gist, sef and 20 others were officially accepted for everyday use as part of the English language.

There was widespread ecstasy generally amongst many Nigerians – both the lettered and the unschooled masses were united in their celebration of this recognition, especially coming from our former colonial masters – because the British that gave us a lingua franca, now were accepting our own languages, our own native words to be part of English language, after several of us were caned by British-tutored Nigerian teachers for speaking “vernacular” in primary schools in those days. You will agree with me that the joy is not unfounded. Filipinos perhaps, felt a similar joy in 2015 when 40 Filipino-coined words and slangs were also added to the Oxford English Dictionary.

Is it also not victory at last, even if in part, for Afrocentric scholars and writers who are foremost critics of the prejudiced nexus between language and power? Several of them have argued vehemently and vowed not to italicise coinages and words from their native languages in their critiques and creative writings. Although they have continued to write in the borrowed languages of French, English and Portuguese. This pseudo victory at least reinforces their stance, showcasing fruits from their activism.

This opening digression was inescapable for me from the dreadful topic of this write-up: Why Yoruba language may become extinct! This is because the Oxford English Dictionary’s action finally forced me to sit down and write this essay that has been pleading for my attention for several months now. Anyway, back to the issue. I could have generalised the topic by saying that several Nigerian languages may become extinct if we don’t make purposeful efforts to halt their adulteration, abuse, disuse and sometimes disdain by their native speakers. Yoruba language in this instance is a euphemism for conquered languages of the world, not just Nigerian or African. It represents languages, whose native speakers are the proletariats in the world order. From prehistoric times to modern days, power relations have always defined human relations; language has remained one of the major instruments of conquest. This is one disorder that the world has not been able to re-order and that may remain with humanity for centuries to come.

Now, you may say Yoruba language is not one of the languages listed as critically endangered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation. Then, it means that you are not getting the point. The viewpoint I am expressing here is that the visible or invincible power of a person or a group of persons over others, determines the norm for all and what is acceptable as public interest, including the language that would be internationally used for socio-political and economic interactions, irrespective of interest of the peripheral groups in their mother tongues or any other issue.

Let’s go memory lane for clarity. Are you aware that the English language is not even native to the English people or the earliest inhabitants of the place known as Britain today? This may shock a number of people except scholars grounded in the history of English language. According to historians, the people of modern day Britain spoke what is known as Celtic language, which itself is a mixture of Indo-European languages. English language as known today to Her Majesty – the Queen, her subjects and ourselves – the emancipated natives of her former colonies, was introduced by “Germanic tribes” said to have invaded Britain sometimes in the 5th century. Although a small populace in the United Kingdom still speak Scottish and Irish languages, which are parts of the Celtic languages, English, the language of the invaders, has remained the flagship of the United Kingdom’s languages. The name England itself has its root from the Germanic tribes.

To further drive home the point that power relations determine accepted language and determine “who gets what, when and how”, as attributed to the political scientist, Harold Lasswell, let me also remind political historians that French was the official language of England for almost 300 years, from mid-11th century to mid-14th century. This was also imposed on England by the invading Normans and French army that defeated the then King Harold II of England, and thereafter forced the people to speak French for official interactions for three centuries.

That Bishop Ajayi Crowther interpreted the English bible into Yoruba language. That J. F. Odunjo’s popular “Iselogunise” Yoruba poem has remained evergreen and known across the globe? That Hubert Ogunde, Moses Olaiya, Idowu Philip, Kola Ogunmola and lot of others promoted Yoruba language through theatre and drama. That even Brazil in faraway South America recognises Yoruba language as one of its official languages. That the Yoruba language has also remained a major language in Nigeria, and it is being used in the Republic du Benin, Togo and even amongst infinitesimal populations of Yoruba people across the globe, may not prevent its extinction!

Recall we are using the Yoruba language as a euphemism for languages not directing world order, and therefore not considered as world power in this discourse. The point is art, literature and public outcries would not save any language from extinction, except its speakers are recognised for their economic power, military prowess, massive scientific innovation, giant strides in Information, Technology and Communication, medical contributions to well-being and wellness of humanity. Such languages may eventually give way.

That is why a German professor, who is very fluent in English language, may come to Nigeria and deliver his speech in German, and except that Nigerians and everyone else follow his/her discourse via the headphone translation devices. And our first class traditional rulers, right on their thrones, would talk to outsiders in English language, rather than also get interpreters to translate their discourse in English, while they speak their native language. That is why akara is known as beans cake amongst non-Yoruba people and not by its Yoruba known name, akara; and pizza is pizza worldwide. That is why our kids would want to learn Spanish, French and in recent times, Mandarin, in addition to English language to increase their access to global opportunities; and be unbothered if they are only able to speak diluted Yoruba language. They may even be less concerned with reading or writing their native language.

The English language itself has survived and continued on its victory lap over the Chinese Mandarin language spoken by 1.3 billion people, because of its continual adoption and adaptation of words and slangs from other languages that are gaining mileages and may compete with it. The adoption of the Nigerian colloquial and words into the English language is therefore not a victory for the Nigerian languages, but the use of linguistic assimilation method by powerful owners of English language to make it remain the language of today, tomorrow and next tomorrow. Records show that the English language has borrowed from about 250 other languages across the globe.

According to UNESCO, over 2,500 languages are vulnerable or already endangered in various degrees, some definitely, others critically. While the Yoruba and a number of other major languages in the underdeveloped countries may not be under serious threat now, their extinction will still come, even if it takes centuries, unless their owners and speakers start making impact in world affairs collectively as a people to the point that they also become dominant stakeholders in the world affairs, vis-à-vis, the world order.

FOLLOW US ON:

PHOTOS & VIDEO: Fire razes part of Ogun free trade zone, Igbesa

Demolition notice: Ogun communities cry out, call for Gov Abiodun’s intervention

Full List Of Countries Nigerians Travel To Without Visa

‘Sleeping Prince’ of Saudi Arabia dies after 20 years in coma

How A Class Of 24 Students Produced 2 Presidents, 4 Governors, 2 Ministers, 4 Emirs, 3 Justices, 4 Ambassadors and Other Influential Leaders

Why Do You Continue To Lie Against Your Motherland? Presidency Calls Out Kemi Badenoch

Trending

-

News9 hours ago

News9 hours agoSERAP Sues INEC Over Alleged ₦55.9 Billion Election Funds Diversion

-

Politics9 hours ago

Politics9 hours agoKano Gov Meets Tinubu In France After Secret Meeting With Kwankwaso

-

News9 hours ago

News9 hours agoPHOTOS & VIDEO: Ekpoma Youths In Edo Attack Fulani Settlements Over Kidnappings

-

News8 hours ago

News8 hours agoFull List Of Countries Nigerians Travel To Without Visa

-

News9 hours ago

News9 hours agoUS Urges Citizens To Leave Venezuela Warns Armed Militias Have Set Up Roadblocks

-

Politics8 hours ago

Politics8 hours agoWhy Buhari Appointed Me As Minister – Lai Mohammed

-

Crime8 hours ago

Crime8 hours agoPHOTOS: NDLEA Nabs 80-Year-Old Drug Lord Again, Intercepts Tramadol-Laced Mannequins

-

News8 hours ago

News8 hours agoDemolition notice: Ogun communities cry out, call for Gov Abiodun’s intervention