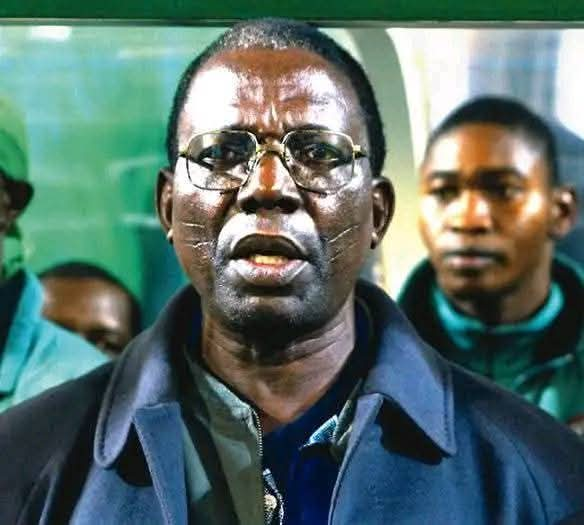

Singer, Omórìnmádé Aníkúlápó-Kútì, known professionally as Mádé Kuti, speaks to NAOMI CHIMA about his career and life as a member of the musically-acclaimed Kuti family

Growing up in a family with music and activism all around you, what were some of your earliest memories of life at the New Afrika Shrine?

One sure memory was when the New Afrika Shrine was opened. This wasn’t the original shrine where Fela performed, but the one my dad, Femi, and my aunt, Yeni, built in 2000. At the opening when I was just about five years old, I played the trumpet. Another vivid memory is of my dad performing four times a week in his 40s. On Fridays, I would sometimes watch him play all night for six hours, then head straight to school in the morning. The shrine gave me freedom. I was a troublemaker — jumping on tables, riding bicycles and skateboards. All my childhood memories of the shrine are happy ones.

Was there ever a time you considered another career besides music?

No! My interest in music developed naturally from all the exposure around me. It could have gone either way, but luckily, I loved it. Every instrument I wanted to learn, someone in my dad’s band taught me the basics. I moved fluidly from one instrument to another — it never felt forced. My dad only told me, “Practice if you want to be a good musician.”

What instrument did you learn first, and how many can you play now?

The first was the trumpet, then sax, piano, guitar, and drums. Between ages 15 and 18, I focused on piano so I could pass an exam for university. After that, I picked up the others again. I now play five comfortably. I tried violin once but never continued.

As someone with afrobeat roots and formal Western training, do you feel a responsibility to blend the two, or do you just let music guide itself?

I let music guide itself. Afrobeat is always the foundation, because it’s the genre I enjoy the most. From there, I allow everything else to flow naturally. I don’t constrain myself. Even on my latest album, you’ll hear a lot of stylistic differences. I am happy with that.

Would you like your children to become musicians?

I would like them to be whatever makes them happy. I just want them to have the same kind of freedom and liberty I had.

Do you think your family name influences the way the audience perceives your music?

I have always considered it a blessing to be part of such an incredible lineage; not just in entertainment, but in medicine, activism, and academics. From Doctor Koye to Doctor Beko, to Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, it is a powerful heritage. I know that whatever I do creatively will always be attributed to the family, and I’m okay with that. However, I wish that people could sometimes take my music as art in itself, beyond the lineage. Yes, afrobeat exists today, thanks to Fela and Femi; but if I wasn’t a Kuti, how would people receive this same music?

Do you feel pressure to outdo your father or grandfather?

Not really. That burden fell more on my father’s shoulders. He had to create his own path while Fela was still at his peak. When my dad released his first hit, ‘Wonder Wonder’, people even claimed Fela wrote it for him. He had to deal with that stigma. My dad, unlike Fela, has always been very protective. He constantly gives me accolades and ensures people know I’m doing my own work.

What is the most important lesson you’ve learnt from your father?

Discipline. My dad worked incredibly hard, practising for long hours before performing. I also saw the struggles he faced touring internationally, especially when musicians used those trips to disappear and never return. This not only disrupted tours but also made it harder for other Nigerian musicians to get visas. That behaviour discouraged many top artists from touring with local bands. It taught me how deeply Nigeria’s circumstances can distort people’s sense of loyalty and responsibility.

How do you approach songwriting, given the political and social themes in your work?

I usually prioritise music first — the texture, instrumentation, and structure — before lyrics. Many of my pieces are instrumental or have minimal lyrics. When I do write, it’s about issues I connect with, like jungle justice or Nigeria’s security failures, as in ‘Story with my Dad’. My latest album is more introspective, focusing on happiness and self-responsibility. It encourages people to stop blaming others and realise that if 200 million Nigerians worked together, real change could happen.

What inspires your stage presence?

It took time to overcome nerves, but experience has been my best teacher. From playing bass and sax in my dad’s band to classical piano recitals and leading my own shows, I grew more confident. Smaller crowds can even be tougher than big ones. Ultimately, I learnt from my dad but refined my style through years of performing.

How do you balance being a husband and a musician?

That’s the easiest part of my life. My wife runs her own clothing brand, but she’s also my personal assistant, handling social media and everything related to my work. She travels with me for international gigs when possible. We are very naturally compatible; no stress or pretense.

How has marrying someone from a different tribe impacted your relationship?

Not at all. My family is already very mixed, and when I met my wife, it wasn’t about ethnicity; it was about values. Only during the last general elections did I notice ethnic tension, but I ignored it. I’d make the same choice a hundred times over.

What do you think Nigerian youths should focus on right now?

Young people need to move away from the distractions of Instagram and TikTok, and focus on resource-based information that helps them grow. Nigeria can either regress into complacency or rise with responsibility.

Do you feel pressure to use music for activism like your father and grandfather?

My grandfather and father did it powerfully. But I ask myself if people really listened. Doing the same thing may not bring new results. My focus is on individual accountability and cultural change. People often ask why I don’t sing about politicians, but what can I say that Nigerians aren’t already saying? If I do it aggressively, it might even seem like pandering. I prefer to sing about what I feel will be effective.

Who are your biggest musical influences?

As a teenager, I was into indie bands like Arctic Monkeys, Muse, Coldplay, and Radiohead. I’ve always been more drawn to instrumentalists than vocalists.

How do you unwind when not making music?

I play football every Saturday at my former school, play chess, relax with family, watch Netflix with my wife, and read.

How has your music evolved over time?

My first album came out before I ever played live. But performing at the Shrine, around Lagos, and internationally has shaped my songwriting. Learning from audience reactions has been my greatest teacher.

What advice do you have for musicians from famous families who want to stand out?

Don’t focus on standing out. Just be yourself and create honestly. I am blessed with access to the Shrine, a space I’ll never take for granted. The beauty of art is that it stands out naturally, even if not immediately appreciated.

How would you describe your relationship with your family?

We are a very close family. My dad, Seun, Aunty Banke, Kunle, Aunty Motun; everyone was around when I turned 30. The family extends beyond the Anikulapo Kuti name. There’s also the Ransome-Kuti side—Aunty Nike, Uncle Dotun—we’re all very connected. Even my grandmother— Remilekun Ransome-Kuti— Fela’s first wife, who just wrote a book; her side of the family is in London, and we always link up whenever we’re there.

What are you most grateful for?

The people I have had around me. I once told someone, “My dad is not a nepo baby,” because he grew up almost totally disenfranchised. Despite having a famous father, Fela publicly shamed him, and he had to teach himself everything, including the saxophone. One of his sisters even suggested he become a fisherman because “there’s more money and opportunity there.” Even now, at 62, my dad practises at least six hours a day. I admire that.

I have joked that we all probably need therapy, but the only reason my dad doesn’t is because he was brutalised and forced his way through life. Unlike him, I had access to the opportunities he wanted, such as studying music. He was pulled out of high school. I can read and write music, and I had great teachers, including my dad and a classical piano teacher from Argentina named Juan. I also had the support of my aunt, who was my guardian in London for seven years. My dad’s guidance even helped me choose the right wife.

I am also grateful for my five younger siblings, none of whom are into music. One wants to be a lawyer, another is into basketball. Ayo, who is popular on Instagram and TikTok, is very different from me.

Do you have any regrets?

Yes. I wish I had practised more when I was younger. I regret jumping from instrument to instrument, instead of learning them one after the other.

What’s the greatest challenge you’ve faced as a musician?

Trying to master your craft is incredibly hard. Some days are good; others are really bad. Instruments like the trumpet are deceptively difficult. It looks innocent, but it’s more demanding than the saxophone because it relies on mouth muscles that weaken quickly. If you skip practice for just three days, your sound suffers.

What’s your favourite food?

I don’t have a favourite anything. That’s my dilemma.

Do you have any other hobby aside from music?

I like cooking. I cooked in London for seven years, and now it’s a hobby. I cook for my wife on Valentine’s Day—more food than I can even eat. I also enjoy cleaning. I’m not obsessive, but I believe if you want to make the world a better place, start with your own space.

At home, no one is allowed to wear shoes inside; we even have signs everywhere. I still do chores, though I don’t really need to anymore, since I now have a community and employees. But growing up, my dad was a stickler for character more than career. He believed if you have good character, everything else will sort itself out.

What has your musical journey been like in recent years?

The past few years have been good to me. I have had opportunities many musicians don’t, but that’s largely thanks to performance income, not recordings or streaming. However, the Lagos music scene is struggling. A lot of venues and gigs have disappeared. The economy’s crumbling, and people can’t afford to pay musicians who don’t pull massive crowds. Many great musicians aren’t getting shows because no one wants to take the risk. So, while I’ve been fortunate, the industry in Nigeria is in a really poor state for most artistes.

What are you working on now?

I just released an album titled, ‘Chapter One: Where Does Happiness Come From?’ It’s an introspective project meant to inspire a mindset shift, not just for Nigerians, but globally. The world feels like it’s entering a dark age, with war, technological dominance, drones, and AI replacing jobs. We are slowly stripping life of its humanity.

I am currently performing and promoting the album. We are in Paris on October 20, Berlin on the 15th, and Montreux, Switzerland, where I’ll be a mentor for three days. After that, I’ll return to Lagos to play at the exhibition at Ecobank, running from October to December. It’s a major showcase of Fela’s legacy, featuring both physical and digital material. I’ll be performing there on October 31.

What do awards and recognitions mean to you?

To me? Not much. But to my career? They’re a great opportunity. Awards don’t make my songs better, but they open doors, bring more attention and credibility.

punch.ng

FOLLOW US ON:

FACEBOOK

TWITTER

PINTEREST

TIKTOK

YOUTUBE

LINKEDIN

TUMBLR

INSTAGRAM