The head of Fusengbuwa Ruling House of Ijebu Ode, in Ogun State, Abdulateef Owoyemi, on Sunday, appealed to Governor Dapo Abiodun to lift the embargo on the Awujale selection process and allow the kingmakers to complete their work.

Owoyemi, a former national president of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Nigeria, said the royal family of Fusengbuwa and the sons and daughters of Ijebu land, both locally and in the diaspora, had become frustrated over the indefinite suspension of the selection process by the government.

Speaking to our correspondent, Owoyemi acknowledged the governor’s support but urged that “no distraction” should prevent the selection of the new Awujale.

“The royal family and indeed every son and daughter of Ijebu land will appreciate it if the governor can allow all of these distractions to be put behind us.

“Ramadan has begun, after which we shall hold our annual Ojude Oba during Eid-el-Kabir, a gathering of significant religious and cultural importance.

“Everyone, both at home and in the diaspora, is waiting, but who will coordinate the preparations? The people are seeking guidance, and the truth is that they want the new Awujale to be installed.

“We want to have this thing over as soon as possible. I receive calls every day from within and outside the country from members of the family who want to know what is happening, but I don’t have anything to say,” he said.

The family head described the kingmakers as “men of integrity, people of character who will not sell the Awujale’s throne for anything.”

He pleaded: “The family is not happy with all that is happening, and we are begging the government to lift the suspension and let us finish this job on time.

“The people are expectant; they want the new Awujale as soon as possible. This process must be completed, and someone must emerge. This is the plea of the Fusengbuwa ruling house.”

The state government had halted the selection process for the second time last month.

A statement signed by the Commissioner for Local Government and Chieftaincy Affairs, Ganiyu Hamzat, explained that the suspension followed a flood of petitions from security agencies and other stakeholders.

On Saturday, the government debunked the rumour that it had endorsed the choice of one Ademorin Aliu Kuye as the new Awujale after his purported selection by the Ifa oracle.

In a statement by Hamzat, the government maintained that the selection process to fill the vacant stool of Awujale remained suspended as announced last month by the government, due to a plethora of petitions that it had received over the selection process.

“The attention of Ogun State Government has been drawn to rumours circulating in certain quarters alleging that the Ifa oracle has chosen Prince Ademorin Aliu Kuye as the next Awujale of Ijebuland and that the state government has endorsed or supported this purported outcome.

“The government wishes to categorically state that it is not involved in, nor has it endorsed, any such claim.

“The process for the selection and installation of the next Awujale of Ijebuland is guided strictly by the applicable laws, established procedures, and recognised traditional customs.

“Any suggestion that the government has adopted or approved a candidate through an oracle or any informal process is false, misleading, and should be disregarded by the public,” the statement read.

The Awujale stool became vacant in July 2025 following the death of 91-year-old Oba Sikiru Adetona, who reigned for 65 years.

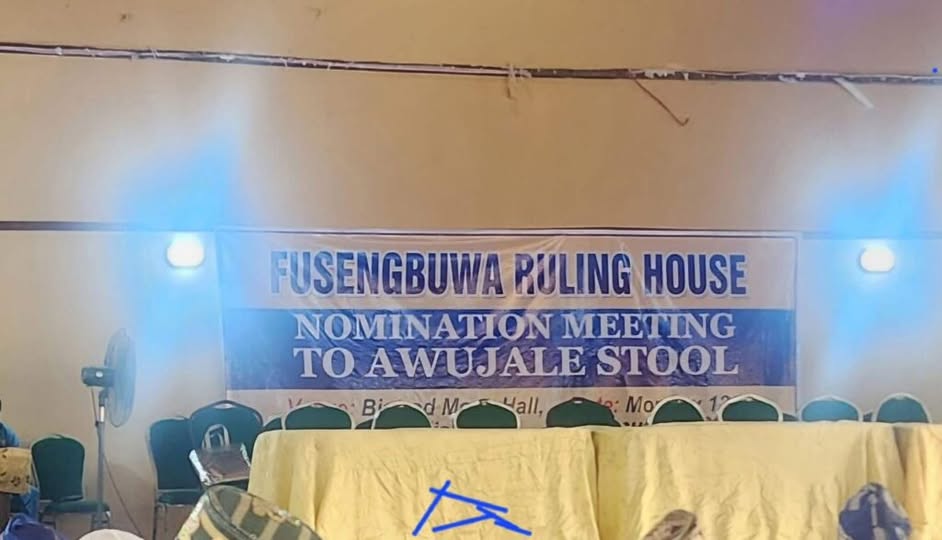

During a recent nomination meeting at Bisrod Hall, GRA Ijebu Ode, 95 candidates, including 94 princes and one princess from Fusengbuwa ruling house, were nominated, and the kingmakers, led by the Ogbeni Oja of Ijebu land, Dr Sunny Kuku, were about to begin the selection process when it was halted.

‘I never paraded myself as Awujale-elect’

The member representing Somolu Federal Constituency of Lagos State in the House of Representatives and one of the contestants for the vacant Awujale stool, Ademorin Aliu Kuye, on Sunday denied ever presenting himself as the Awujale-elect.

Kuye stated that he was never desperate to become the next Awujale and emphasised that, as a federal lawmaker and lawyer of 37 years, he would never engage in acts that contravened existing laws.

He also distanced himself from a viral song reportedly produced by a female waka singer praising him as the Awujale-elect, saying he believed the song was created by detractors to tarnish his reputation.

Kuye spoke while responding to allegations made by the princes and princesses of the Fusengbuwa ruling house of Ijebu Ode.

In a statement signed by Kunle Johnson Adebajo, the royal family accused Kuye of parading himself as the Awujale-elect and of commissioning a song in his praise.

The family said: “We want to state without equivocation that the action of the said Hon Kuye is illegal and capable of causing chaos and unrest in Ijebuland.

“For clarity and the avoidance of doubt, Hon Kuye’s action violates Ijebuland and Ogun State’s chieftaincy and customary laws as well as proper succession procedures.

“We, as princes and princesses of the Fusengbuwa ruling house, the royal family qualified to produce the next Awujale of Ijebuland, make bold to say that Hon Kuye’s claim of being the Awujale-elect borders on pretence to a stool he has not been selected for.

“This is also a gross violation of the customary law, infractions which should be viewed seriously by the appropriate authorities and met with appropriate sanction and punishment.

“We therefore call on the Ogun State Government to stop this charade by Hon Kuye and his supporters. They should be immediately called to order; to desist from further violations of the law regarding the filling of the vacant Awujale stool.”

Kuye, in a phone interview with our correspondent, maintained that the allegations were baseless and reiterated his commitment to lawful conduct.

He explained: “I have never been involved in any of their allegations, and I am also part of the princes and princesses of the Fusengbuwa ruling house.

“I know nothing about what they are saying, and my family has also issued a statement on my behalf saying that nobody should be allowed to do such a thing and that we are totally in support of the position of the state government on this matter.

“The truth is that I am never desperate about becoming the next Awujale. I was never interested. It was my family that bought the form for me, and for over a month, I never filled it out until they did. How could I then be behaving as if I am desperate or must become Awujale at all costs? So it is all baseless accusations.”

On the viral song, Kuye said: “I don’t know about the production of any song. I know that this could be the handiwork of my opponent because I never commissioned anybody to do that song.

“I am saying it with all sense of responsibility, and if anybody or any musician has something contrary, let the person come out.

“In fact, I didn’t know about the song. I didn’t hear it until people started complaining about it, so I suspect that it must have come from these detractors. We know what they are capable of.”

He further highlighted his public service record, saying, “I am a lawmaker and a lawyer of 37 years. I have been chairman of a local government, a commissioner, a special adviser to the President, and a two-term member of the House of Representatives representing the people of Somolu.

“I am an institutional person, I know what is right to do, and I won’t do less.”

punch.ng

FOLLOW US ON: